about the bookabout

Gasping for breath in a cattle truck occupied by 119 other men, a young Spaniard captured fighting with the French Resistance counts off the days and nights as the train rolls slowly but inexorably towards Buchenwald.

On the five seemingly endless days of the journey, he talks to an unnamed Frenchman from Semur. Sometimes the conversation sends him into daydreams about his childhood; sometimes he looks into the future and the nightmare setting in which his friend's memory will come back to haunt him.

When at last the concentration camp's Wagnerian gates come into sight, 'the guy from Semur' dies suddenly and inexplicably and the young Spaniard has to face the camp alone.

“The diabolical plot of this extraordinary novel was supplied by the Nazis, who had no idea that Jorge Semprun would use it one day for purposes both humane and cautionary. The Cattle Truck is a work of fiction founded on unimaginable fact.”

—Paul Bailey

“A beautiful translation ... Semprun waited almost 20 years before writing the story of a Spanish teenager who fought in the Maquis in France, was captured by the Germans and sent as a Red, a political prisoner, a non-Jew, to Buchenwald. He gives us a different perspective on hell and the power and glory of the human spirit.”

—Martha Gellhorn, Books of the Year, Daily Telegraph

“The cattle truck is of course one of the most evocative images of the Holocaust. This book describes one man's experience of a journey in one, but it extends far beyond the confines of the truck to explore themes of personal and collective responsibility.”

—John Jacobs, Jewish Chronicle

“Tells the story of the slow journey into hell made by dissidents and undesirables who were sentenced to deportation by the Nazi invaders of France. Semprun, a Spaniard, was a member of the French Resistance and was himself arrested and deported to Buchenwald. In this extraordinary novel he gives an account of a similar journey, told by "Gerard" several years later, who relives significant incidents as the trip plays over in his mind.

This novel is the more harrowing for what it represents and the way the nightmare vision of the death camps is revealed in moments of simple recognition. The effectiveness of Gerard's sudden memory of a child taking a smaller one's hand as they are made to race from their murders cannot be underestimated.”

—Moy McCrory, The Times

“His concerns are highlighted by conversations with other forced passengers, particularly "the guy from Semur", and with German guards, with whom he communicated in their own language. This creates some of the most moving moments in the book, when the ability to communicate finally overcomes any indiscriminate elimination of the "other" and allows Semprun the ultimate magnanimity: the power to award life, not death, to an enemy.

Everything in this book is multi-dimensional, reflecting forward as well as back. The beauty of a beech tree is as timelessly vital as the agony of the journey. And the journey is one that goes beyond the transit from Compiegne to Buchenwald, or even from youth to imposed maturity. For Semprun, from the age of seventeen, was fighting in two of the great European conflicts of this century and for its apparently clearest moral causes.

That he did so as a volunteer and not a victim renders him a freedom fighter in both senses of the phrase. That he is prepared to use hindsight blended with memory renders him brave in another sense, as he reviews earlier convictions and draws fresh conclusions. That he is also a passionate and philosophical writer renders his books essential reading. Many of them have been missed for too long: make this one unmissable.”

—Amanda Hopkinson, New Statesman

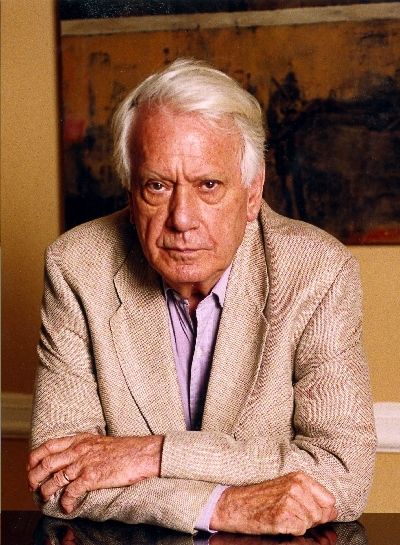

About The Author / Editor