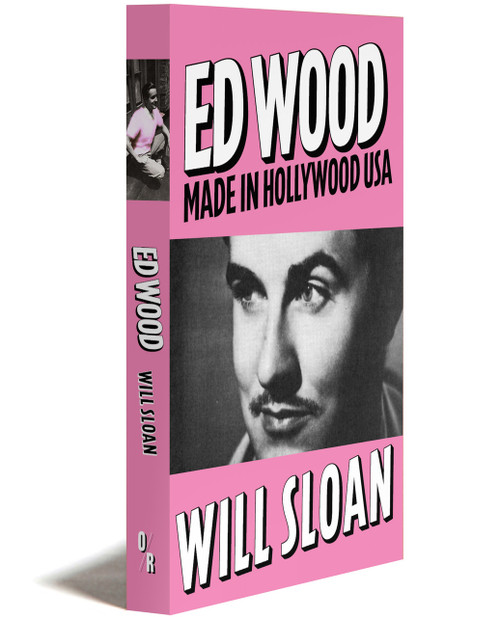

Ed Wood

“Beautifully written, intelligently funny, packed with surprising facts on every page, and composed with a sensitive love for his subject that is neither cultishly worshipful nor patronizing for the sake of a laugh.”

—Guy Maddin“Will Sloan’s complex, deep-dive examination of this unique and eccentric filmmaker is now the definitive book on the often maligned Ed Wood.”

—Drew Friedman“It’s finally here: The ultimate completist take on the films and literature of Ed Wood.”

—Owen Kline“The book we have always needed on Ed Wood. Will Sloan does away with easy distinctions of ‘bad’ and ‘good’ art and finds a much more useful category of criticism: ‘fascination’.”

—Willow Maclay“Such thought-provoking analyses add up to a captivating portrait of an 'accidental avant-gardiste.' Fans of movies so bad they’re good won’t be disappointed.”

—Publishers Weeklyabout the bookabout

When Edward D. Wood, Jr. died in 1978 at fifty-four, just days after being evicted from his home, he was largely forgotten. Two years later, he was named “Worst Director of All Time”—a title that cemented his cult status. By the time a youthful Johnny Depp starred in an eponymous movie about the filmmaker in 1994, Wood’s low-budget films including Plan 9 from Outer Space, Glen or Glenda, and Bride of the Monster, had become beloved “so bad they’re good” classics. Since then, rediscovered works and shifting cultural attitudes have led new audiences to embrace his eccentric style and ahead-of-his-time takes on gender and genre.

Ed Wood: Made in Hollywood USA is a critical reappraisal that takes Wood seriously, positioning him as a true independent who blurs the lines between high and low art. Will Sloan traces his marginal career—from Bela Lugosi collaborations to pornographic films—and explores how Wood’s chaotic sets, fading stars, and taboo subjects created something singular. Placing his films in their cultural context, Sloan reveals how Wood fused grindhouse with avant-garde, nostalgia with innovation, and failure with vision. Marking the centennial of Wood’s birth, this engaging take is both a timely investigation into the politics of taste and a loving tribute to a defiant outsider artist.

“Will Sloan has masterfully constructed a truly compelling, humorous and scholarly appreciation of Ed Wood’s oeuvre, maintaining that his poverty-row productions represent surreal ‘dreamscapes.’ It’s the most important work on Ed Wood yet, and an immensely entertaining must-read for anyone who loves bad movies.”

—Harry & Michael Medved, The Golden Turkey Awards

About The Author / Editor

Preview

A police car drives along a dusty road somewhere on the edge of the San Fernando Valley. It slows and parks next to a wooded area, where a cemetery is said to be just out of frame. Cut to the car halting in an entirely different area. Day has become night, the thick forest is reduced to a few shrubs and saplings, and so many cardboard tombstones are scattered so randomly on the ground that it’s impossible to imagine the coffins fitting beneath them. This sequence of events occurs many times in Plan 9 from Outer Space, and passing from the “real” world to Ed Wood’s fake one is like crossing over from our world to another.

We spend a lot of time in that cemetery across Plan 9’s seventy-nine minutes. Strange incidents have been occurring there. Two gravediggers were found dead, and Inspector Daniel Clay (Tor Johnson) was killed during his investigation. Bordering the cemetery is the house of an ordinary young couple, airline pilot Jeff Trent (Gregory Walcott) and his wife Paula (Mona McKinnon), who share an ambivalence about their spooky neighborhood. On the many nights when Jeff is away on duty, Paula is left alone, and on one such night, a mysterious old man (Bela Lugosi/Tom Mason) invades her bedroom. She flees to the cemetery, where she is terrorized by two more mysterious figures: the old man’s wife (Maila “Vampira” Nurmi) and Inspector Clay, both resurrected from the dead.

If Wood hoped to create a fake cemetery that could blend seamlessly with the real one we see in pick-up shots, he failed. There is no sense of depth and geography. We see Paula running through the same few feet of set over and over. The actors struggle to contort around the tombstones and greenery, packed so tightly together. Everything casts shadows against the black sky. The studio floor keeps peeking out between the patches of artificial grass, and when characters fall to the ground, the ground shifts with them. When Edgar G. Ulmer had to recreate Manhattan on the cheap for his film Detour (1945), he created an evocative city of memory, shrouding a mostly empty soundstage in thick fog; Wood also uses fog to create atmosphere, but for no better reason than desperation, without understanding that less can be more.

And yet. . . like the nocturnal netherworld of Jail Bait, the Plan 9 cemetery becomes a beautiful dream space. Certainly, it’s more distinctive than the dreary offices and living rooms of so many more “competent,” less memorable sci-fi films of the era. It may not match the ambience of Ulmer’s Manhattan, but like that set, Wood’s cemetery is spartan enough to force viewers to fill in the blanks. Imagine the effect this unheralded film must have had on the imaginations of the kids who grew up watching it on television. Imagine what it must have been like to stumble upon this movie without any explanation, divorced from the years of accumulated lore about its production.

So, yes, the Plan 9 cemetery is bad—but again, it’s not merely bad. Spending so much time there without any sense of the layout, one starts feeling lost in a void with no beginning or end. When Wood cuts together shots of actors traversing the same few feet of set, it’s like time and space are standing still. That the actors treat their surreal surroundings with stone-faced seriousness enhances the feeling of a dream. This tension is a big part of what makes Plan 9 still so compelling to those of us who are long immune to the shock of the film’s many obvious flubs. The set is clearly fake, but while we’re looking at it, it’s hard to remember what “real” looks like.

in the media

Ed Wood

“Beautifully written, intelligently funny, packed with surprising facts on every page, and composed with a sensitive love for his subject that is neither cultishly worshipful nor patronizing for the sake of a laugh.”

—Guy Maddin“Will Sloan’s complex, deep-dive examination of this unique and eccentric filmmaker is now the definitive book on the often maligned Ed Wood.”

—Drew Friedman“It’s finally here: The ultimate completist take on the films and literature of Ed Wood.”

—Owen Kline“The book we have always needed on Ed Wood. Will Sloan does away with easy distinctions of ‘bad’ and ‘good’ art and finds a much more useful category of criticism: ‘fascination’.”

—Willow Maclay“Such thought-provoking analyses add up to a captivating portrait of an 'accidental avant-gardiste.' Fans of movies so bad they’re good won’t be disappointed.”

—Publishers Weeklyabout the bookabout

When Edward D. Wood, Jr. died in 1978 at fifty-four, just days after being evicted from his home, he was largely forgotten. Two years later, he was named “Worst Director of All Time”—a title that cemented his cult status. By the time a youthful Johnny Depp starred in an eponymous movie about the filmmaker in 1994, Wood’s low-budget films including Plan 9 from Outer Space, Glen or Glenda, and Bride of the Monster, had become beloved “so bad they’re good” classics. Since then, rediscovered works and shifting cultural attitudes have led new audiences to embrace his eccentric style and ahead-of-his-time takes on gender and genre.

Ed Wood: Made in Hollywood USA is a critical reappraisal that takes Wood seriously, positioning him as a true independent who blurs the lines between high and low art. Will Sloan traces his marginal career—from Bela Lugosi collaborations to pornographic films—and explores how Wood’s chaotic sets, fading stars, and taboo subjects created something singular. Placing his films in their cultural context, Sloan reveals how Wood fused grindhouse with avant-garde, nostalgia with innovation, and failure with vision. Marking the centennial of Wood’s birth, this engaging take is both a timely investigation into the politics of taste and a loving tribute to a defiant outsider artist.

“Will Sloan has masterfully constructed a truly compelling, humorous and scholarly appreciation of Ed Wood’s oeuvre, maintaining that his poverty-row productions represent surreal ‘dreamscapes.’ It’s the most important work on Ed Wood yet, and an immensely entertaining must-read for anyone who loves bad movies.”

—Harry & Michael Medved, The Golden Turkey Awards

About The Author / Editor

Preview

A police car drives along a dusty road somewhere on the edge of the San Fernando Valley. It slows and parks next to a wooded area, where a cemetery is said to be just out of frame. Cut to the car halting in an entirely different area. Day has become night, the thick forest is reduced to a few shrubs and saplings, and so many cardboard tombstones are scattered so randomly on the ground that it’s impossible to imagine the coffins fitting beneath them. This sequence of events occurs many times in Plan 9 from Outer Space, and passing from the “real” world to Ed Wood’s fake one is like crossing over from our world to another.

We spend a lot of time in that cemetery across Plan 9’s seventy-nine minutes. Strange incidents have been occurring there. Two gravediggers were found dead, and Inspector Daniel Clay (Tor Johnson) was killed during his investigation. Bordering the cemetery is the house of an ordinary young couple, airline pilot Jeff Trent (Gregory Walcott) and his wife Paula (Mona McKinnon), who share an ambivalence about their spooky neighborhood. On the many nights when Jeff is away on duty, Paula is left alone, and on one such night, a mysterious old man (Bela Lugosi/Tom Mason) invades her bedroom. She flees to the cemetery, where she is terrorized by two more mysterious figures: the old man’s wife (Maila “Vampira” Nurmi) and Inspector Clay, both resurrected from the dead.

If Wood hoped to create a fake cemetery that could blend seamlessly with the real one we see in pick-up shots, he failed. There is no sense of depth and geography. We see Paula running through the same few feet of set over and over. The actors struggle to contort around the tombstones and greenery, packed so tightly together. Everything casts shadows against the black sky. The studio floor keeps peeking out between the patches of artificial grass, and when characters fall to the ground, the ground shifts with them. When Edgar G. Ulmer had to recreate Manhattan on the cheap for his film Detour (1945), he created an evocative city of memory, shrouding a mostly empty soundstage in thick fog; Wood also uses fog to create atmosphere, but for no better reason than desperation, without understanding that less can be more.

And yet. . . like the nocturnal netherworld of Jail Bait, the Plan 9 cemetery becomes a beautiful dream space. Certainly, it’s more distinctive than the dreary offices and living rooms of so many more “competent,” less memorable sci-fi films of the era. It may not match the ambience of Ulmer’s Manhattan, but like that set, Wood’s cemetery is spartan enough to force viewers to fill in the blanks. Imagine the effect this unheralded film must have had on the imaginations of the kids who grew up watching it on television. Imagine what it must have been like to stumble upon this movie without any explanation, divorced from the years of accumulated lore about its production.

So, yes, the Plan 9 cemetery is bad—but again, it’s not merely bad. Spending so much time there without any sense of the layout, one starts feeling lost in a void with no beginning or end. When Wood cuts together shots of actors traversing the same few feet of set, it’s like time and space are standing still. That the actors treat their surreal surroundings with stone-faced seriousness enhances the feeling of a dream. This tension is a big part of what makes Plan 9 still so compelling to those of us who are long immune to the shock of the film’s many obvious flubs. The set is clearly fake, but while we’re looking at it, it’s hard to remember what “real” looks like.