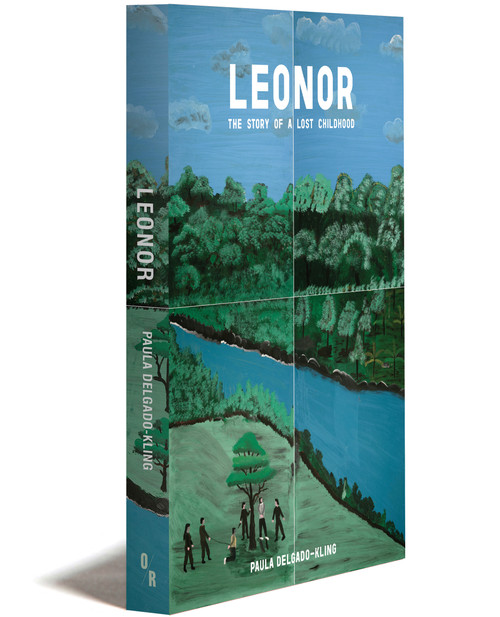

Leonor

“A compelling firsthand account of the greed, social neglect, and deliberate misrule that has forced many Latin American children and families to seek a better life in the arms of terrorist groups.”

—Ernesto Quiñonez“[A] devastating portrait of unspeakable suffering.”

—Kirkus“[Delgado-Kling] spares no one and condemns no one, writing about the country and the people she loves with honesty, grit and generosity. I couldn’t put this book down.”

—Luis Jaramillo, author of The Witches of El Pasoabout the bookabout

Set in the author’s homeland, Colombia, this is the heartbreaking story of Leonor, former child soldier of the FARC, a rural guerrilla group. Paula Delgado-Kling followed Leonor for nineteen years, from shortly after she was an active member of the FARC forced into sexual slavery by a commander thirty-four years her senior, through her rehabilitation and struggle with alcohol and drug addiction, to more recent days as the mother of two girls. Leonor’s physical beauty, together with resourcefulness and imagination in the face of horrendous circumstances, helped her carve a space for herself in a male-dominated world. She never stopped believing that she was a woman of worth and importance. It took her many years of therapy to accept that she was also a victim. Throughout the story of Leonor, Delgado-Kling interweaves the experiences of her own family, involved with Colombian politics since the 19th century and deeply afflicted, too, by the decades of violence there.

“The contrasts between Delgado-Kling’s and Leonor’s lives are stark, but the author’s capacity to bridge that distance both indicates her ambition as a writer and serves as a reminder of the utter pervasiveness of trauma.”

—EMILY NEMENS, author of The Cactus League

About The Author / Editor

Preview

I could not reconcile that had I been born in Leonor’s hamlet and not in Bogotá, her life might have been mine.

Friends asked me: What kind of friendship can you have with a guerrillera?

As I did every few months, I dialed Leonor’s telephone number, one of many she gave me through the years. If she picked up, and she was alone, she might feel free to talk. It was a cell phone, her boyfriend’s, perhaps. Even after Commander Tico’s abuse, Leonor always had a boyfriend, or a lover, or a fling. During the sunshine of her youth, from the way she put herself together—the girl certainly had powers to make a T-shirt allude to the fantasy of a ball gown—grown men desired her. With age and a more mature perspective dawning, she dismissed men who had passed through her life for the scavengers they were.

The dial tone confirmed the call was going through. I knew she would be limping towards the phone, the hand with the L tattoo on the wrist reaching for the receiver.

“Hola, Paula. Nunca usted se imaginará!” she said. In her voice were stalling inflections inherent of her region in Southern Colombia. There had been a death in her family, but she was equally concerned that her girls’ puppy was lost. The puppy made Rosa and Dahlia happy.

Leonor’s voice revealed her frenzied state—”Dios mio! Tanto ha pasado.” The phone connection echoed her nervous giggles.

Since early morning she was scouting every street in Mocoa to find the puppy. Leonor was like other mothers, who found meaning and responsibility in caring for children, and who would do whatever it took to shield them; this was remarkable given all the anguish she had endured from early age. Leonor’s tender disposition persisted over the time I knew her. We aged. Leonor’s beauty vanished. Drained from her was the glowy youth, the cheery display. Instead, in her smile, I detected disenchantment and faded hope. We were—now—both mothers, and it was heartwarming to hear that her Rosa and Dahlia were healthy and attending school. We both were occupied with dinners to cook, laundry to wash, the tidying up. Keeping up theatrics was beyond us. We set mere minutes aside for me to telephone, stealing some time, until one of our daughters beckoned—she was hungry, and could she get some paper and crayons to draw? Or she wanted to change the channel on the TV, because there was again the story of La Llorona. Our girls’ fears were the same.

According to legend, the phantom La Llorona makes ominous appearances under the moonlight by a lake or a river. Her crying conveys the pain borne by mothers.

Porqué llora?

She drowned her children and so she weeps.

Farmers speak of her when kneading bread or mending clothes.

She is a native. Tall and dark-haired.

I heard she is white.

She spooks the animals in the darkness of the night.

Words exchanged in whispers, even when there is no one who might overhear. At times of lassoing cattle in the open plains. Or when pushing past the tediousness of plucking feathers off a chicken.

She shows up to abduct our children. To replace hers, the ones she herself drowned. That is why she weeps.

No. The woman weeps for all of our lost children.

She is most often spotted in the lonesomest of places.

in the media

Leonor

“A compelling firsthand account of the greed, social neglect, and deliberate misrule that has forced many Latin American children and families to seek a better life in the arms of terrorist groups.”

—Ernesto Quiñonez“[A] devastating portrait of unspeakable suffering.”

—Kirkus“[Delgado-Kling] spares no one and condemns no one, writing about the country and the people she loves with honesty, grit and generosity. I couldn’t put this book down.”

—Luis Jaramillo, author of The Witches of El Pasoabout the bookabout

Set in the author’s homeland, Colombia, this is the heartbreaking story of Leonor, former child soldier of the FARC, a rural guerrilla group. Paula Delgado-Kling followed Leonor for nineteen years, from shortly after she was an active member of the FARC forced into sexual slavery by a commander thirty-four years her senior, through her rehabilitation and struggle with alcohol and drug addiction, to more recent days as the mother of two girls. Leonor’s physical beauty, together with resourcefulness and imagination in the face of horrendous circumstances, helped her carve a space for herself in a male-dominated world. She never stopped believing that she was a woman of worth and importance. It took her many years of therapy to accept that she was also a victim. Throughout the story of Leonor, Delgado-Kling interweaves the experiences of her own family, involved with Colombian politics since the 19th century and deeply afflicted, too, by the decades of violence there.

“The contrasts between Delgado-Kling’s and Leonor’s lives are stark, but the author’s capacity to bridge that distance both indicates her ambition as a writer and serves as a reminder of the utter pervasiveness of trauma.”

—EMILY NEMENS, author of The Cactus League

About The Author / Editor

Preview

I could not reconcile that had I been born in Leonor’s hamlet and not in Bogotá, her life might have been mine.

Friends asked me: What kind of friendship can you have with a guerrillera?

As I did every few months, I dialed Leonor’s telephone number, one of many she gave me through the years. If she picked up, and she was alone, she might feel free to talk. It was a cell phone, her boyfriend’s, perhaps. Even after Commander Tico’s abuse, Leonor always had a boyfriend, or a lover, or a fling. During the sunshine of her youth, from the way she put herself together—the girl certainly had powers to make a T-shirt allude to the fantasy of a ball gown—grown men desired her. With age and a more mature perspective dawning, she dismissed men who had passed through her life for the scavengers they were.

The dial tone confirmed the call was going through. I knew she would be limping towards the phone, the hand with the L tattoo on the wrist reaching for the receiver.

“Hola, Paula. Nunca usted se imaginará!” she said. In her voice were stalling inflections inherent of her region in Southern Colombia. There had been a death in her family, but she was equally concerned that her girls’ puppy was lost. The puppy made Rosa and Dahlia happy.

Leonor’s voice revealed her frenzied state—”Dios mio! Tanto ha pasado.” The phone connection echoed her nervous giggles.

Since early morning she was scouting every street in Mocoa to find the puppy. Leonor was like other mothers, who found meaning and responsibility in caring for children, and who would do whatever it took to shield them; this was remarkable given all the anguish she had endured from early age. Leonor’s tender disposition persisted over the time I knew her. We aged. Leonor’s beauty vanished. Drained from her was the glowy youth, the cheery display. Instead, in her smile, I detected disenchantment and faded hope. We were—now—both mothers, and it was heartwarming to hear that her Rosa and Dahlia were healthy and attending school. We both were occupied with dinners to cook, laundry to wash, the tidying up. Keeping up theatrics was beyond us. We set mere minutes aside for me to telephone, stealing some time, until one of our daughters beckoned—she was hungry, and could she get some paper and crayons to draw? Or she wanted to change the channel on the TV, because there was again the story of La Llorona. Our girls’ fears were the same.

According to legend, the phantom La Llorona makes ominous appearances under the moonlight by a lake or a river. Her crying conveys the pain borne by mothers.

Porqué llora?

She drowned her children and so she weeps.

Farmers speak of her when kneading bread or mending clothes.

She is a native. Tall and dark-haired.

I heard she is white.

She spooks the animals in the darkness of the night.

Words exchanged in whispers, even when there is no one who might overhear. At times of lassoing cattle in the open plains. Or when pushing past the tediousness of plucking feathers off a chicken.

She shows up to abduct our children. To replace hers, the ones she herself drowned. That is why she weeps.

No. The woman weeps for all of our lost children.

She is most often spotted in the lonesomest of places.