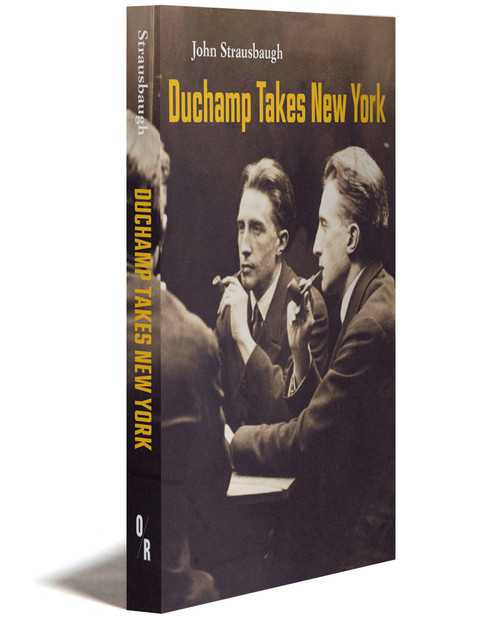

Duchamp Takes New York

“Well-researched, beautifully written, jargon-free, focused, smart, lucid, concise, charming, witty. An absolute delight.”

—Kurt Andersen“Strausbaugh, a masterful explorer of New York’s vivid past, turns his keen eye now on how the city’s art and culture were transformed by Marcel Duchamp. ”

—Richard Byrne“Defines the man and the moment that pushed the art world beyond 'the tyranny of good taste' and helped it find true power.”

—Ilise S. Carterabout the bookabout

Artist, anti-artist, joker, trickster, shape-shifter: Marcel Duchamp broke with tradition and pushed the avant-garde decisively forward. When his work exploded like an art bomb in New York in the 1910s, American art was still mired in the nineteenth century. Duchamp, bored with tradition, reimagined what art could be, what it was for, and how it might be made—hanging a snow shovel from the ceiling, inverting a urinal, “painting” with dust and bits of string between panes of glass, and reducing his entire oeuvre into a briefcase of miniatures. Duchamp Takes New York traces this bold, playful energy, showing how the city inspired and staged his avant-garde experiments.

Duchamp's offhand gestures reshaped the course of twentieth-century American art, laying the groundwork for nearly every major movement that followed. And then, at the height of his influence, Duchamp appeared to walk away—declaring himself finished with art and devoting his energies to becoming a chess champion instead. Only after his death did it emerge that he had spent two decades secretly working on one final, unsettling work, leaving the world to try to comprehend it without explanation—his ultimate prank.

John Strausbaugh, a longtime chronicler of the city, puts New York at the center of Duchamp’s story. Fleeing the comforts of French bourgeois life—“wives, three children, a country house, three cars!”—Duchamp found New York instantly liberating. It was here that he produced much of his most radical work and eventually settled for good, once declaring, “New York itself is a complete work of art.” Duchamp's art simply can't be pinned down, without first recognizing his relationship to New York.

About The Author / Editor

Preview

It took Duchamp until the following summer, June 1942, to reach New York, after arranging to ship the supplies to make fifty Boxes, which he was counting on for income. He was about to turn fifty-five. Unlike Man Ray, he was delighted to be back. And why not? While Paris would be a Nazi-infested ghost town until the end of the war, wartime New York was a boomtown, starting a climb that would take it to the apex of its twentieth-century trajectory. From the postwar years into the ’60s, no city on the planet rivaled it for wealth, influence, or prestige. Among other factors, with Paris shut down, New York took over again as the art capital of the West and held that crown much longer this time than it had earlier in the century. Along with Duchamp and Ernst, the cream of European creative and intellectual life had fled the Nazis for New York. Their collective impact on New York’s culture was going to be incalculable. Fulfilling what Duchamp had said to the press back in 1915, the ruins of Europe were the past, New York was the future.

Even though he was still insisting he wasn’t an artist anymore, Duchamp was right where he needed to be. He’d make vacation trips to Europe, but Manhattan was now his permanent home for the rest of his life. He would become a naturalized citizen in 1955. In New York, during the last decades of his life, Duchamp’s legend as the visionary who dynamited the old definitions of art would bloom, and he helped it along, the slightly aloof éminence grise of his own legacy.

in the media

Duchamp Takes New York

“Well-researched, beautifully written, jargon-free, focused, smart, lucid, concise, charming, witty. An absolute delight.”

—Kurt Andersen“Strausbaugh, a masterful explorer of New York’s vivid past, turns his keen eye now on how the city’s art and culture were transformed by Marcel Duchamp. ”

—Richard Byrne“Defines the man and the moment that pushed the art world beyond 'the tyranny of good taste' and helped it find true power.”

—Ilise S. Carterabout the bookabout

Artist, anti-artist, joker, trickster, shape-shifter: Marcel Duchamp broke with tradition and pushed the avant-garde decisively forward. When his work exploded like an art bomb in New York in the 1910s, American art was still mired in the nineteenth century. Duchamp, bored with tradition, reimagined what art could be, what it was for, and how it might be made—hanging a snow shovel from the ceiling, inverting a urinal, “painting” with dust and bits of string between panes of glass, and reducing his entire oeuvre into a briefcase of miniatures. Duchamp Takes New York traces this bold, playful energy, showing how the city inspired and staged his avant-garde experiments.

Duchamp's offhand gestures reshaped the course of twentieth-century American art, laying the groundwork for nearly every major movement that followed. And then, at the height of his influence, Duchamp appeared to walk away—declaring himself finished with art and devoting his energies to becoming a chess champion instead. Only after his death did it emerge that he had spent two decades secretly working on one final, unsettling work, leaving the world to try to comprehend it without explanation—his ultimate prank.

John Strausbaugh, a longtime chronicler of the city, puts New York at the center of Duchamp’s story. Fleeing the comforts of French bourgeois life—“wives, three children, a country house, three cars!”—Duchamp found New York instantly liberating. It was here that he produced much of his most radical work and eventually settled for good, once declaring, “New York itself is a complete work of art.” Duchamp's art simply can't be pinned down, without first recognizing his relationship to New York.

About The Author / Editor

Preview

It took Duchamp until the following summer, June 1942, to reach New York, after arranging to ship the supplies to make fifty Boxes, which he was counting on for income. He was about to turn fifty-five. Unlike Man Ray, he was delighted to be back. And why not? While Paris would be a Nazi-infested ghost town until the end of the war, wartime New York was a boomtown, starting a climb that would take it to the apex of its twentieth-century trajectory. From the postwar years into the ’60s, no city on the planet rivaled it for wealth, influence, or prestige. Among other factors, with Paris shut down, New York took over again as the art capital of the West and held that crown much longer this time than it had earlier in the century. Along with Duchamp and Ernst, the cream of European creative and intellectual life had fled the Nazis for New York. Their collective impact on New York’s culture was going to be incalculable. Fulfilling what Duchamp had said to the press back in 1915, the ruins of Europe were the past, New York was the future.

Even though he was still insisting he wasn’t an artist anymore, Duchamp was right where he needed to be. He’d make vacation trips to Europe, but Manhattan was now his permanent home for the rest of his life. He would become a naturalized citizen in 1955. In New York, during the last decades of his life, Duchamp’s legend as the visionary who dynamited the old definitions of art would bloom, and he helped it along, the slightly aloof éminence grise of his own legacy.