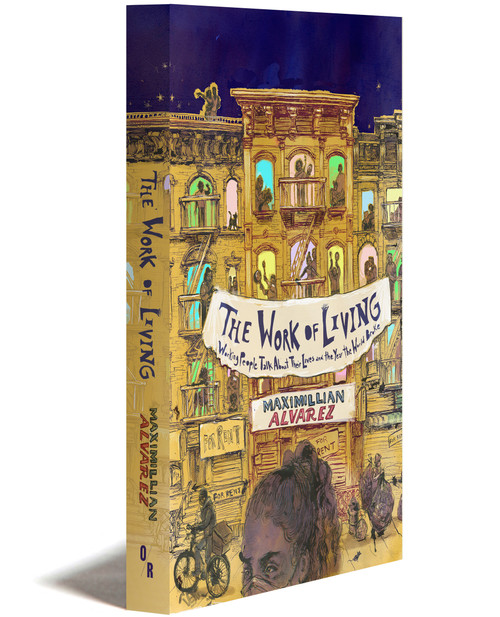

The work of living

“A magnificent scholar… [with] a powerful vision and a subtle analysis at the same time… So much to offer.”

—Dr. Cornel West, Professor of Philosophy and Christian Practice, Union Theological Seminaryabout the bookabout

As COVID-19 swept across the globe with merciless force, it was working people who kept the world from falling apart. Deemed “essential” by a system that has shown just how much it needs our labor but has no concern for our lives, workers sacrificed—and many were sacrificed—to keep us fed, to keep our shelves stocked, to keep our hospitals and transit running, to care for our loved ones, and so much more. But when we look back at this particular moment, when we try to write these days into history for ourselves and for future generations, whose voices will go on the record? Whose stories will be remembered?

In late 2020 and early 2021, at what was then the height of the pandemic, Maximillian Alvarez conducted a series of intimate interviews with workers of all stripes, from all around the US—from Kyle, a sheet metal worker in Kentucky; to Mx. Pucks, a burlesque performer and producer in Seattle; to Nick, a gravedigger in New Jersey. As he does in his widely celebrated podcast, Working People, Alvarez spoke with them about their lives, their work, and their experiences living through a year when the world itself seemed to break apart. Those conversations, documented in these pages, are at times meandering, sometimes funny or philosophical, occasionally punctured by pain so deep that it hurts to read them.

Filled with stories of struggle and strength, fear and loss, love and rage, The Work of Living is a deeply human history of one of the defining events of the 21st century told by the people who lived it.

“Maximillian Alvarez doesn’t just report; he listens like an organizer, and pulls the fundamental challenges of humanity from the people he interviews so that it’s never just about storytelling or setting a narrative. It’s about finding what really binds us together in those struggles so that we can fight our way forward with real love and solidarity.”

—Sara Nelson, International President, Association of Flight Attendants-CWA

“Maximillian Alvarez is a once in a generation talent. Brandishing his pen like a Machetero brandishes a machete, he combines journalistic integrity and revolutionary fervor in a way that strikes right at the heart of the oppressor. His writing not only gives voice to the voiceless but paints their dreams and aspirations in a clear and vivid way, leaving the reader reborn and baptized in the historic global struggle for solidarity and justice.”

—Kooper Caraway, President, South Dakota Federation of Labor, AFL-CIO

About The Author / Editor

Preview

History does not happen in broad strokes, nor is it made by a few powerful people; the stories we tell about the past just make it seem that way. Living in a society that has systematically disempowered so many of us for the sake of empowering and enriching so few, it is hard to believe it’s an accident that we have been taught to see history as something that certain special individuals shape and that the vast, unspecial many merely experience. I certainly hope that a viral event like the COVID-19 pandemic has made clear that the reality is always much more complex and, well, messy. True, from deadly and catastrophic decisions made (or not made) by heads of state like Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, Jair Bolsonaro, and Narendra Modi, to the decisions made (or not made) by city mayors, state governors, influential media personalities, bosses, corporate executives at pharmaceutical companies, prison wardens, etc., certain individuals have had a major hand in shaping the nightmarish unfolding of events—and must be held accountable for their crimes. But that is only part of the story. Each of us played a role as well. For big and small reasons—some tied to the particularities of our lives and personal histories, others to the pressures our economic realities put on us or the imprint our collective (national, local, and political) cultures leave on us—we all acted and engaged one another in certain ways over these past two years that directly contributed either to the virus spreading and hurting people or to us being able to contain it; that made it possible for us to care for each other and hold society together, or made it easier for things to fall apart. Many of us sacrificed (willingly or by force) to keep the world from collapsing, while many others took advantage of people’s suffering. My point is that the deadly, contagious virus that has spread throughout the world by way of the bodies of millions of people has shown us, in the most morbidly literal way, how much of an impact we have on the world and people around us (and vice versa).

What can the history of such a world-shaking event be—how much can that history actually tell us and future generations—if it leaves no record of the kind of intimate experiences, stories, thoughts, feelings, memories, and impressions that make history human? How much can we actually understand what this pandemic was and all that it will mean for the carrying on of humanity if we relegate these things to the periphery of what’s historically important? Again, I put this book together in the hope that the people, stories, and conversations in it will offer an answer: not much. This is why this book is built the way it is, why its conversations unfold the way they do—at times meandering, sometimes funny or philosophical, at other times punctured by pain and fear so deep that it hurts to read. This is also why the stories of every worker I spoke to for this book—from Kyle, a sheet metal worker in Kentucky, to Mx. Pucks, a burlesque performer and producer in Seattle, to Nick, a gravedigger in New Jersey—go way beyond the jobs they do for a living (though we talk about those, too). In the same way that I’ve tried from the very start of my podcast Working People to talk to workers not just about their jobs but about their lives—where they come from, what their families are like, what memories they hold dear, what they think about thorny political questions—I have tried to approach every conversation I recorded for this book in a way that will make it impossible for reader to ignore the whole human being behind every name tag they see, the precious life behind all the “essential work” our lives depend on.

in the media

The work of living

“A magnificent scholar… [with] a powerful vision and a subtle analysis at the same time… So much to offer.”

—Dr. Cornel West, Professor of Philosophy and Christian Practice, Union Theological Seminaryabout the bookabout

As COVID-19 swept across the globe with merciless force, it was working people who kept the world from falling apart. Deemed “essential” by a system that has shown just how much it needs our labor but has no concern for our lives, workers sacrificed—and many were sacrificed—to keep us fed, to keep our shelves stocked, to keep our hospitals and transit running, to care for our loved ones, and so much more. But when we look back at this particular moment, when we try to write these days into history for ourselves and for future generations, whose voices will go on the record? Whose stories will be remembered?

In late 2020 and early 2021, at what was then the height of the pandemic, Maximillian Alvarez conducted a series of intimate interviews with workers of all stripes, from all around the US—from Kyle, a sheet metal worker in Kentucky; to Mx. Pucks, a burlesque performer and producer in Seattle; to Nick, a gravedigger in New Jersey. As he does in his widely celebrated podcast, Working People, Alvarez spoke with them about their lives, their work, and their experiences living through a year when the world itself seemed to break apart. Those conversations, documented in these pages, are at times meandering, sometimes funny or philosophical, occasionally punctured by pain so deep that it hurts to read them.

Filled with stories of struggle and strength, fear and loss, love and rage, The Work of Living is a deeply human history of one of the defining events of the 21st century told by the people who lived it.

“Maximillian Alvarez doesn’t just report; he listens like an organizer, and pulls the fundamental challenges of humanity from the people he interviews so that it’s never just about storytelling or setting a narrative. It’s about finding what really binds us together in those struggles so that we can fight our way forward with real love and solidarity.”

—Sara Nelson, International President, Association of Flight Attendants-CWA

“Maximillian Alvarez is a once in a generation talent. Brandishing his pen like a Machetero brandishes a machete, he combines journalistic integrity and revolutionary fervor in a way that strikes right at the heart of the oppressor. His writing not only gives voice to the voiceless but paints their dreams and aspirations in a clear and vivid way, leaving the reader reborn and baptized in the historic global struggle for solidarity and justice.”

—Kooper Caraway, President, South Dakota Federation of Labor, AFL-CIO

About The Author / Editor

Preview

History does not happen in broad strokes, nor is it made by a few powerful people; the stories we tell about the past just make it seem that way. Living in a society that has systematically disempowered so many of us for the sake of empowering and enriching so few, it is hard to believe it’s an accident that we have been taught to see history as something that certain special individuals shape and that the vast, unspecial many merely experience. I certainly hope that a viral event like the COVID-19 pandemic has made clear that the reality is always much more complex and, well, messy. True, from deadly and catastrophic decisions made (or not made) by heads of state like Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, Jair Bolsonaro, and Narendra Modi, to the decisions made (or not made) by city mayors, state governors, influential media personalities, bosses, corporate executives at pharmaceutical companies, prison wardens, etc., certain individuals have had a major hand in shaping the nightmarish unfolding of events—and must be held accountable for their crimes. But that is only part of the story. Each of us played a role as well. For big and small reasons—some tied to the particularities of our lives and personal histories, others to the pressures our economic realities put on us or the imprint our collective (national, local, and political) cultures leave on us—we all acted and engaged one another in certain ways over these past two years that directly contributed either to the virus spreading and hurting people or to us being able to contain it; that made it possible for us to care for each other and hold society together, or made it easier for things to fall apart. Many of us sacrificed (willingly or by force) to keep the world from collapsing, while many others took advantage of people’s suffering. My point is that the deadly, contagious virus that has spread throughout the world by way of the bodies of millions of people has shown us, in the most morbidly literal way, how much of an impact we have on the world and people around us (and vice versa).

What can the history of such a world-shaking event be—how much can that history actually tell us and future generations—if it leaves no record of the kind of intimate experiences, stories, thoughts, feelings, memories, and impressions that make history human? How much can we actually understand what this pandemic was and all that it will mean for the carrying on of humanity if we relegate these things to the periphery of what’s historically important? Again, I put this book together in the hope that the people, stories, and conversations in it will offer an answer: not much. This is why this book is built the way it is, why its conversations unfold the way they do—at times meandering, sometimes funny or philosophical, at other times punctured by pain and fear so deep that it hurts to read. This is also why the stories of every worker I spoke to for this book—from Kyle, a sheet metal worker in Kentucky, to Mx. Pucks, a burlesque performer and producer in Seattle, to Nick, a gravedigger in New Jersey—go way beyond the jobs they do for a living (though we talk about those, too). In the same way that I’ve tried from the very start of my podcast Working People to talk to workers not just about their jobs but about their lives—where they come from, what their families are like, what memories they hold dear, what they think about thorny political questions—I have tried to approach every conversation I recorded for this book in a way that will make it impossible for reader to ignore the whole human being behind every name tag they see, the precious life behind all the “essential work” our lives depend on.